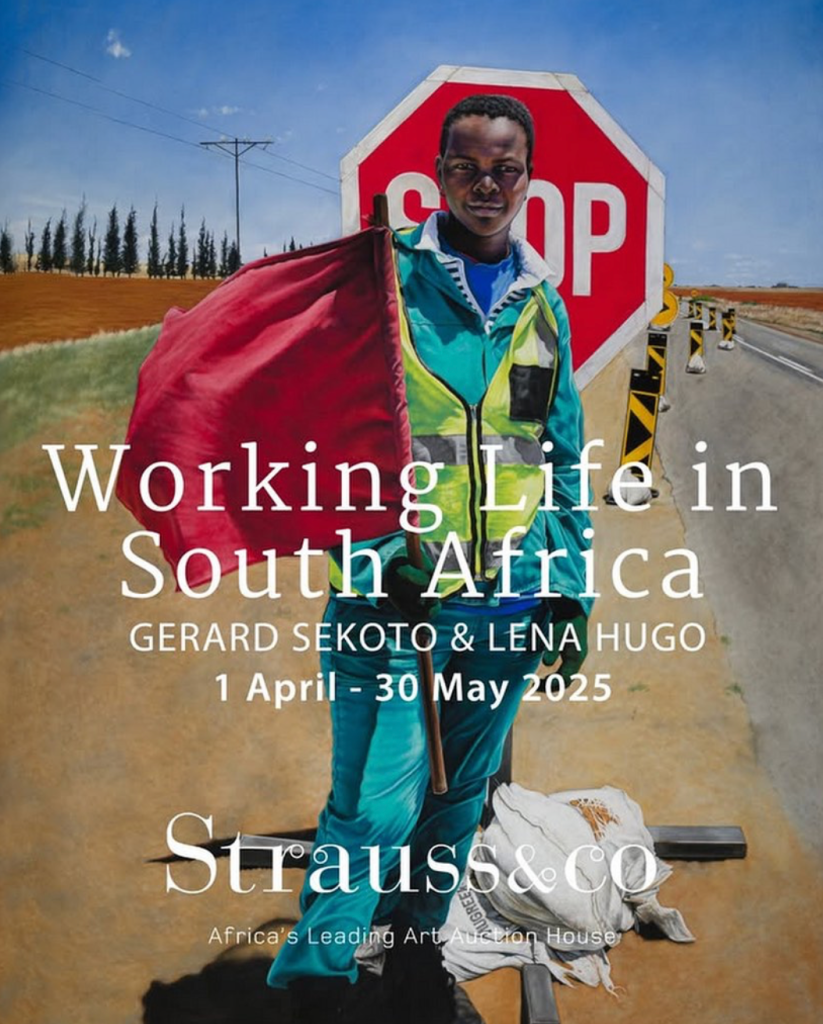

Still on show (and now extended until the 3rd of June) for just a few more days, Head Curator and Senior Art Specialist Wilhelm van Rensburg has brought artists Gerard Sekoto and Lena Hugo into a rare, intergenerational dialogue on labour and dignity with the exhibition Working Life in South Africa: Gerard Sekoto & Lena Hugo. This powerful exhibition explores the role of the worker in shaping South Africa’s cultural and economic story.

We spoke to Wilhelm about the sparks behind this curation, Sekoto’s international renaissance, and the quiet power of seeing labour with fresh eyes.

Pairing Gerard Sekoto (1940s) and Lena Hugo (21st century) is fascinating. What inspired this dialogue across time, and what fresh conversations do you hope it sparks about South African labor and resilience?

[WILHELM]: Strauss & Co is auditing the extensive art collection of the University of Johannesburg, and some of the most striking and important works are the three early Sekoto works in the Nimrod Ndebele collection, on permanent loan to the University. When one thinks of Sekoto’s work, his township scenes come readily to mind, but I wanted a sharper focus, and on inspecting these three works, I noticed that all three deal with the common worker: a garbage collector, a fruit seller, and builders and brickmakers, and that was the spark I needed to conceptualize the exhibition. I also recall seeing a magnificent exhibition of Lena Hugo’s workers at the UJ Art Gallery in 2010, and the rest, as they say, is history. There is a tremendous synergy between these two artists, and that is what I wanted to explicate.

Sekoto’s self-portrait is currently in the Paris Noir exhibition after its Venice Biennale debut and this show highlights his South African roots. How do you see the local and international art worlds shaping his legacy differently?

[WILHELM]: The main reason for what I want to call the current ‘Sekoto Fever’, is the fact that the global art world is only now waking up to the tremendous importance of what in art historical terms is called Black Modernism, or Modernist African Art. Sceptics of Contemporary African Art doubt its validity until it is pointed out to them that Contemporary African Art has extremely strong antecedents, in the shape of African Modernism of the 1930s, 40s and 50s, Sekoto is one of the top three Black Modernism, in such lustrous company as Ernest Mancoba, and the Nigerian, Ben Enwonwu. African modernism is of course a big gap in the international art exhibition circuit, and galleries all over the world must do some redress.

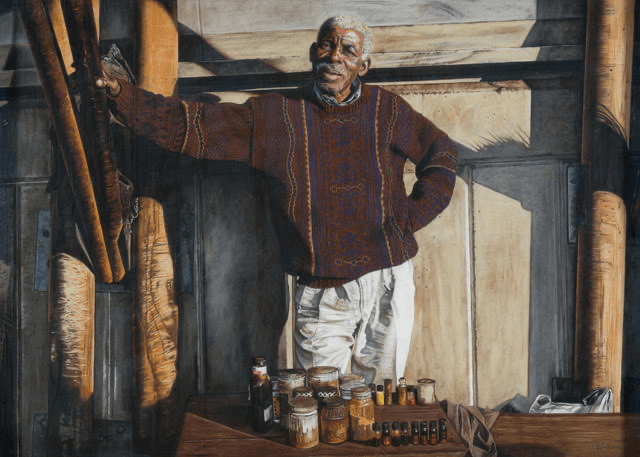

Both artists depict labour but decades apart. What’s the most striking difference or similarity between Sekoto and Hugo’s depictions that you want people to notice?

[WILHELM]: The commonality is of course that both artists depict the common worker, usually the everyday unskilled worker, focusing the viewer’s attention on the important and often unrecognised work that they do in the economy. The main difference between the two is that Sekoto depicts the urban Black worker of the 1930s and 40s. The discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886 led to large-scale migration to the mine fields, migrant workers having to make a new life for themselves in the cities. Lena Hugo, on the other hand, catapults us into the 21stcentury with her depiction of heavy machinery operators, typical of semi- and fully skilled workers. Sekoto’s work tends to be smaller in scale and more intimate, whereas Hugo’s are large-scale, life-size figures done in phenomenal hyper realistic, almost photorealistic style, all in pastel!

“The Mother on the Road” is a standout piece. Why was it essential to include here, and what does it tell us about Sekoto’s view of work and survival?

[WILHELM]: The painting is what we call an important ‘pre-exile’ work. Sekoto went into self-imposed exile in 1947, briefly to London and then onto Paris where he stayed the rest of his life, dying in 1993. He never visited South Africa again, but he did attend an arts festival in Dakar, Senegal in 1966. This experience inspired the wonderful, and regal, ethereal Senegalese women he painted at the time. The pre-exile work is highly sought after and usually fetch very high prices on auction. Also, the work is repatriated from Australia, and so we are celebrating a veritable Sekoto homecoming at the same time!

You’re both a curator and a specialist in South African art. What continues to surprise or move you when revisiting Sekoto’s work in the context of today’s art landscape?

[WILHELM]: What is surprising for me is how versatile Sekoto was in the use of his subject matter. There is an infinite variety of ways in which a curator can engage with his work, constantly pulling out different themes from his work. The worker was particularly striking for me because we often forget how important the worker is in our lives. The show also happens to fall un 1 May, International Workers Day. As an art historian, I was also surprised to see the many depictions of the worker in art over the past two centuries, starting with the Realists in the mid-19th century, then, the depiction of the worker during the 1917 Russian Revolution, and later, in the 1930s the Mexican Revolution. Also, South African artists portraying the worker in their art: Dorothy Kay, David Goldblatt, Mary Sibande, and even William Kentridge in his well-known public sculpture, The Fire Walker in downtown Johannesburg.

For a first-time viewer of Sekoto and Hugo’s work, what’s the one thing you’d want them to feel or remember after this exhibition?

[WILHELM]: Respect for the common worker! Look him or her in the eye and see the person behind the facade. Hugo’s portraits and faces are particularly expressive of their sitters’ personalities, and Sekoto’s workers are stoically and indefatigably getting on with the job, making a living for themselves and taking care of their families.

Through this thoughtful pairing of Sekoto’s historic scenes and Hugo’s modern-day portraits, Wilhelm van Rensburg reminds us that the stories of workers, past and present, are not just background details but vital cultural narratives. This exhibition is a call to honour the hands that build, grow, and carry society, and to see art as a living bridge between memory and momentum. Go experience the now extended exhibition before Tuesday the 3rd of June.

Featured image(s): Supplied

![[GUIDE] Everything You Need To Know Ahead Of The 2026 Grammys](https://lamag.africa/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/laplugs-culture-insights-2-grammys.png?w=1024)

Leave a Reply